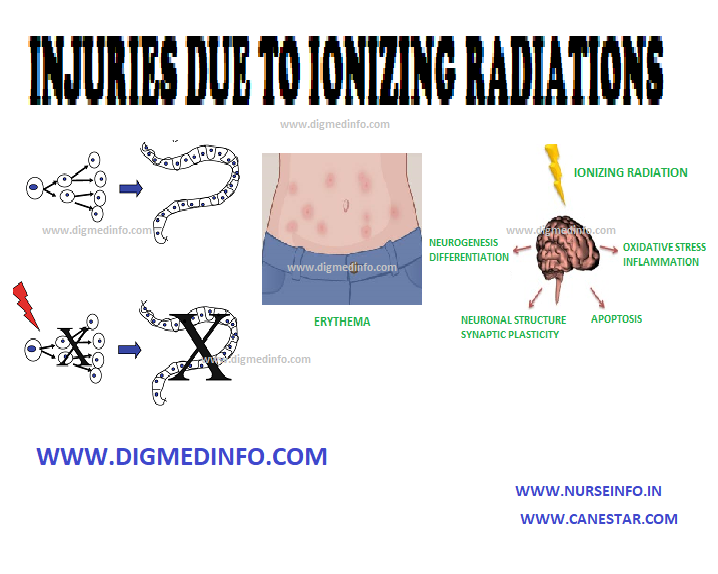

INJURIES DUE TO IONIZING RADIATIONS – General Considerations, Acute Radiation Syndrome, Damage to Embryo by Irradiation in Fetal Life and Local Radiation Injury

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Ionizing radiations are either electromagnetic or particulate in nature. They are derived from natural or artificial radioactive isotopes, nuclear reactors, diagnostic and therapeutic equipment (e.g. X-rays, CT scan) and the complex shower of particles from the outer space known as cosmic rays. The radiations include alpha, beta, and gamma particles and electromagnetic waves.

Radiation injury is seen in survivors of nuclear war, after radiotherapy, persons engaged in industries involving radioactive materials, radiologists and radiotherapists. In some parts of the world, radioactive sand accounts for low dose continuous radiation. Radiation is harmful at all doses, the danger increasing with the rate and dose of exposure. The age group 10-19 years is most susceptible. The maximal permissible radiation exposure for occupationally exposed workers is 0.1 rem per week for the whole body.

Critical targets are the cellular nuclei.

The damage caused to the biological systems is of two types:

- Direct absorption of radiation energy results in the formation of H+ ion, OH– ion and hydrogen peroxide which all interfere with enzyme systems.

- Direct injury to chromosomes lead to chromosomal breaks and abnormal cross links in the DNA or between the DNA and cellular proteins. Dividing cells are more susceptible to radiation injury. The effects may be: (1) delay in mitosis, (2) reduction in the number of dividing cells, and (3) chromosomal changes.

The effects of radiation vary according to the degree and nature of exposure. Massive radiation exposure causes immediate effects, while small repeated exposures induce response that may not be perceived even for years. When the dose is large and exposure is extensive over the body, the acute radiation syndrome results. Excessive dosage delivered locally gives rise to localized damage, e.g., radiation dermatitis, radiation nephritis etc.

Pathological changes

Radiation leads to arrest of mitotic activity, which progresses to cell damage and death. Tissues, which have a high rate of cell division such as bone marrow, intestinal epithelium and germinal cells of gonads, suffer most. Secondary complications include infection, hemorrhage and fibrosis. Loss of epithelium, neutropenia and depression of immune response favor bacterial invasion and septicemia. Infective lesions are most evident in the oropharynx and intestines. The brain and spinal cord are more sensitive to radiation than peripheral nerves.

ACUTE RADIATION SYNDROME

Acute exposure of the whole body to 300 cGy is fatal. Lethal doses produce maximal effects on the bone marrow and the intestinal epithelium. With high doses, intestinal lesions predominate over marrow toxicity. With still higher doses neurological features such as disorientation, convulsions and shock predominate. Except in the fulminant neurological type of injury, the classical form occurs in four phases:

Phase 1

This phase occurs within minutes of exposure and is characterized by nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. Reduction in lymphocytes may occur in 24-30 hours due to direct destruction of these cells.

Phase 2

There is a latent period of about a week after which the third stage develops.

Phase 3

During this critical phase there is marrow failure leading to neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, which result in secondary infection and hemorrhage. Fever, vomiting, diarrhea, oropharyngeal ulceration, and purpura may be seen.

Phase 4

The survivors enter the fourth (recovery) phase in which the symptoms subside.

Temporary sterility may develop and persist for up to one year. Risk of developing malignancies such as chronic myeloid leukemia, cancers of the breast, thyroid, lungs and digestive organs is considerably increased in such persons.

Treatment

It is supportive and aims at:

1. Correcting toxemia and infections,

2. Correcting fluid and electrolyte imbalances and

3. Treating hemorrhagic manifestations, profound anemia and neutropenia.

These patients are preferably managed in an aseptic environment. Adequate antibiotic therapy and transfusion of neutrophils and platelets are life saving. Hemopoetic factors such as filgrastim and sargamostim help in the recovery of blood cells. Blood stem cell transplantation and bone marrow transplantation may be may be needed later.

DAMAGE TO EMBRYO BY IRRADIATION IN FETAL LIFE

Irradiation during stage of implantation results in fetal death. During the stage of organogenesis, fetal malformation or abortion may result. After three months, by which time, the main organs would have formed, gross deformities are not produced, but stunting of growth, reduction of life span, sterility and tendency to develop leukemias and cancers have been noted. Radiation dose as low as 5 cGY can injure the growing fetus. The irradiation given out by modern X-ray machines for skiagram of the chest is only 1/100 cGY.

LOCAL RADIATION INJURY

Erythema develops over the area of exposure within days or weeks after acute exposure and this may progress to epidermolysis. Late complications are atrophy of the skin, subcutaneous fibrosis, telangiectasia, and later hyperkeratosis. These hyperkeratotic lesions may develop malignancy later.