BRONCHIAL ASTHMA – General Characteristics, Pathology, Clinical Features, Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention

General Characteristics

The term ‘asthma’ in Greek means ‘breathless’ or ‘breathe with open mouth.’ Asthma is a common chronic inflammatory condition of the airways whose mechanism is not completely understood yet. Epidemiological studies suggest that multiple genetic and environmental factors contribute to the causation of asthma, a clinical condition that is viewed as a cluster of related disorders. Genetic factors contribute to the variability with regard to age of onset, sensitivity of environmental causes and response to treatment.

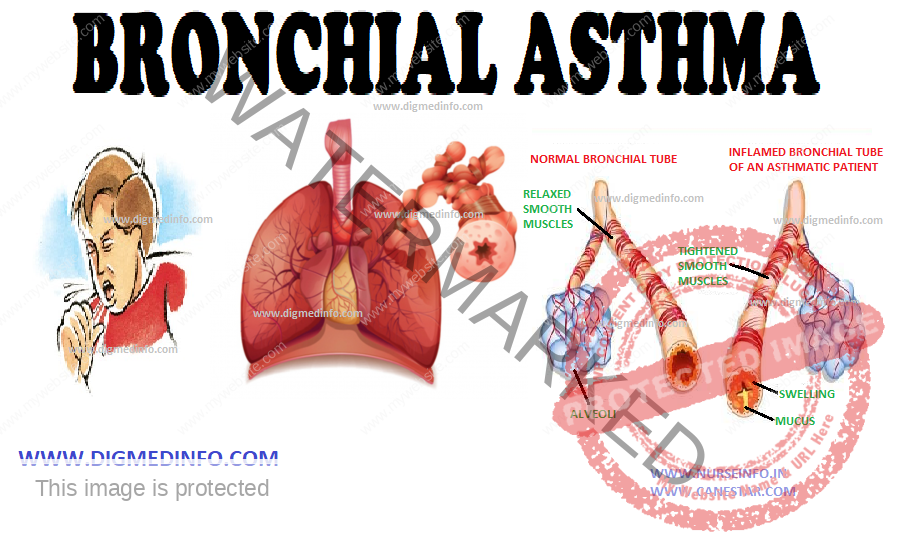

Airway inflammation is associated with airway hyperresponsiveness, airflow limitation, and respiratory symptoms. Airway inflammation leads to limitation of airflow by acute bronchoconstriction, edema of the airway wall, formation of mucus plugs, and airway remodelling.

The tracheobronchial tree reveals increased responsiveness to immunological and non-immunological factors. Several organic dusts, fumes, and chemicals precipitate immunological mechanisms. Non-immunological stimuli include thermal, chemical or psychological factors.

Bronchial asthma used to be classified into the extrinsic (atopic) and intrinsic (cryptogenic) types. In the former an external precipitating factor is identifiable, whereas in the latter, it is not. The antigens include ingested, inhaled or parenterally administered substances.

The serum of such individuals may show elevated levels of specific antibodies belonging to the IgE and sometimes IgG classes. Persons developing extrinsic asthma have other atopic manifestations like eczema. The dermatological and respiratory manifestations show a see-saw relationship. In many cases family history of bronchial asthma may be present. Extrinsic asthma generally sets in by the age of 10-15 years. This type has a better prognosis from the point of response to therapy and mortality. The age of onset for intrinsic asthma is after 30 years. Precipitating causes or raised antibody levels are not evident but these patients show a higher frequency of eosinophilia, aspirin sensitivity, and nasal polyposis. Common stimuli which precipitate extrinsic asthma are inhaled allergens like house dust, pollens, fungi, animal hairs, insect scales and industrial fumes, and foods and drugs which are consumed in day-to-day life. Once sensitization occurs, these antigens release chemical mediators from the mast cells by interacting with the IgE molecules on their surface. Type I hypersensitivity reaction ensues. Asthma can also be caused by Type III (delayed) hypersensitivity mechanism mediated by IgG. In some individuals both Type I and Type III reactions occur, the former leading to an immediate asthmatic paroxysm and the latter leading to a delayed episode.

Exercise-induced asthma is a problem in children and young adults, in which bronchoconstriction is provoked by various forms of exercise such as running or climbing stairs, but others such as swimming may not do so. Provocation of bronchoconstriction by cold inspired air is a possibility in such cases. In many cases the attacks are brought on straight by the exercise, but in the others asthma sets in several hours after the exercise. The mechanism is a Type I hypersensitivity reaction. Short acting β2-agonists are used to prevent exercise- induced asthma. Inhaled steroids are indicated and are useful. Systemic steroids are seldom necessary.

PATHOLOGY

Inflammation of the airways is brought on by several factors. Eosinophils, T-lymphocytes (CD4+), macrophages and mast cells infiltrate the bronchial wall. The epithelium is vacuolated and the ciliated cells desquamate. Several cellular factors play their roles in the inflammatory process. Neuropeptides such as bradykinins, substance P and neurotensin A lead to bronchoconstriction and excessive secretion of mucus.

The main chemical transmitters, which alter the airways, are histamine, prostaglandin and leukotrienes. These lead to contraction of bronchial muscle, increase in vascular permeability and excessive secretion of abnormal mucus. Airway inflammation persists for several years. Its severity correlates with the severity of asthma. Hyperresponsiveness of the inflamed airways is aggravated by autonomic and neural mechanisms. The final result is obstruction of the small and medium sized airways brought about by mucosal edema, tenacious mucus and bronchoconstriction.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The attacks start with dyspnea (often at rest), expiratory wheeze, and cough. The onset is abrupt in most cases. These attacks may occur seasonally or during all times of the year (perennial asthma). The attacks may last for several hours if untreated. Severity of the paroxysm varies. In the moderately severe case the patient is orthopneic and cyanosed, and the accessory muscles of respiration are active. There may be ineffective cough with only very scanty and tenacious mucoid expectoration. The asthmatic paroxysm in many individuals is ushered in by a bout of coughing and sneezing on exposure to the allergen. The pulse is rapid. Blood pressure is normal or elevated. In severe cases pulsus paradoxus may occur. Expansion of the chest is considerably diminished, often to less than 2 cm during the attack. The diagnostic feature of bronchial asthma is the presence of expiratory wheeze heard all over the chest.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of bronchial asthma is clinical. The history of sudden attack of paroxysmal dyspnea, cough, and the auscultatory hallmark of expiratory wheeze heard all over the chest are diagnostic. Long duration of complaints, history of allergy, and positive family history are other helpful clinical points.

Clinical features which indicate severe ventilatory Impairment

1. Inability to narrate history continuously or severe distress even on mild exertion,

2. Cyanosis, flapping tremors,

3. Mental confusion,

4. Respiratory rate above 25/minute,

5. Heart rate persistently above 110/minute.

6. Inspiratory fall in blood pressure exceeds 16 mm Hg,

7. PEFR less than 40% of predicted value, and

8. Feeble breath sounds.

Differential diagnosis:

Bronchial asthma has to be differentiated from other causes of paroxysmal dyspnea. These include chronic bronchitis emphysema syndrome (CBES), acute left-sided heart failure, acute bronchitis, tropical pulmonary eosinophilia, metabolic acidosis, and tracheal obstruction by foreign bodies or tumours.

It is important to distinguish left-sided heart failure (cardiac asthma) from bronchial asthma. Left-sided heart failure complicates valvular heart disease, systemic hypertension or ischemic heart disease. It causes paroxysmal dyspnea in the first half of the night whereas bronchial asthma is more common in the early hours of the morning.

In bronchial asthma there is generalized wheeze all over the chest, whereas in cardiac failure, basal crepitations are more prominent, though generalized bronchospasm may also be evident at times. In heart failure, gallop rhythm may be evident. Careful search for the underlying disease may reveal the etiology.

TREATMENT

Treatment may be described under three heads: (1) treatment of the acute attack; (2) treatment in between attacks; and (3) treatment of acute severe asthma.

TREATMENT OF THE ACUTE ATTACK

At present the drugs of choice employed to stop an acute attack are beta 2-agonist drugs. They act mainly on the bronchial muscle as relaxants without much effect on the cardiovascular system. These include salbutamol, terbutaline, salmeterol, bambuterol and others. These can be given orally, as inhalations (aerosol or powder) or parenterally. The oral dose is effective within 15-20 minutes and the action lasts for 4-6 hours.

Nebulizers, which can be carried by the patient or operated in the emergency room, are available for administration of these drugs. These can deliver larger doses as required. The drug solution is nebulized by passing oxygen or air under pressure through it.

PREVENTION

It is important to avoid known allergens, which can be identified. In the case of some allergens like house dust and pollen, desensitization can be achieved by repeated challenges.

Inhaled corticosteroids 200-800 micro g per day has been recommended as the treatment of choice for regular preventive therapy of asthma.

Yoga and controlled breathing exercises are of considerable benefit in allaying the paroxysms.