RESPIRATORY FAILURE – Classification, Etiology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestation, Diagnostic Evaluation and Management

INTRODUCTION

The most important function of the respiratory system is to provide oxygen to the body tissues and remove the carbon dioxide. The body relies primarily on the central nervous system, the pulmonary system, the heart, and the vascular system to accomplish the effective respiration. Respiratory failure develops when one or more of these systems or organs fail to maintain optimal functioning.

Respiratory failure is a sudden and life-threatening deterioration of the gas exchange functions of the lung and indicates failure of the lungs to provide adequate oxygenation or ventilation for the blood. Acute respiratory failure is defined as the decrease in the arterial oxygen tension to less than 50 mm Hg (hypoxemia) and increase in the arterial carbon dioxide tension, i.e. (hypercapina) to greater than 50 mm Hg, with the arterial pH of less than 7.35. it is a condition in which there is inadequate gas exchange by the respiratory system, with the result that arterial O2 and CO2 levels cannot be maintained within their normal ranges.

DEFINITION

- Acute respiratory failure is a condition in which the patient’s breathing apparatus fails in the ability to maintain arterial blood gases within the normal range.

- Ventilatory failure is the inability of the body to sustain respiratory drive or the inability of the chest wall and muscles to mechanically move air in and out of the lungs. The hallmark of ventilator failure is an elevated CO2 level.

- A sudden inability of the lungs to maintain normal respiratory function. The condition may be caused by an obstruction in the airways or by failure of the lungs to exchange gases in the alveoli.

- Acute respiratory failure is defined as the decrease in the arterial oxygen tension to less than 50 mm Hg (hypoxemia) and increase in the arterial carbon dioxide tension, i.e. (hypercapnia) to greater than 50 mm Hg, with an arterial pH of less than 7.35.

CLASSIFICATION OF RESPIRATORY FAILURE

It is divided into two types:

- Acute respiratory failure

- Chronic respiratory failure

Acute Respiratory Failure

Acute respiratory failure is characterized by hypoxemia (PaO2 less than 50 mm Hg) and academia (pH less than 7.35). acute respiratory failure occurs rapidly, usually in minutes to hours or days

Types of Acute Respiratory Failure

It is divided into two:

- Type 1 acute respiratory failure

- Type 2 acute respiratory failure

- Type 1 acute respiratory failure: Type 1 respiratory failure is defined as hypoxia without hypercapnia and indeed the PaCO2 may be normal or low. It is typically caused by a ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) mismatch, the volume of air flowing in and out of the lungs is not matched with the flow of blood to the lungs.

- Type 2 acute respiratory failure: Type 2 respiratory failure is caused by inadequate ventilation, both oxygen and carbon dioxide are affected and buildup of carbon dioxide levels (PaCO2) that has been generated by the body.

Chronic Respiratory Failure

Chronic respiratory failure is characterized by hypoxemia and hypercapnea with the normal pH (7.35 to 7.45). chronic respiratory failure occurs over a period of months to a year – allows for activation of compensatory mechanism.

Chronic respiratory failure may also be divided into:

- Hypoxemic respiratory failure: when a lung disease causes respiratory failure, gas exchange is reduced because of changes in ventilation (the exchange of air between the lungs and the atmosphere), perfusion (blood flow), or both. Activity of the respiratory muscles is normal. This type of respiratory failure which results from a mismatch between ventilation and perfusion is called hypoxemic respiratory failure. Some of the alveoli get less fresh air than they need for the amount of blood flow, with the net result of a fall in oxygen in the blood. These patients tend to have more difficulty with the transport of oxygen than with removing carbon dioxide. They often overbreathe (hyperventilate) to make up for the low oxygen, and this results in a low CO2 level in the blood (hypocapnia). Hypocapnia makes the blood more basic or alkaline which is injurious to the cells.

- Hypercapnic respiratory failure: respiratory failure due to a disease of the muscles used for breathing (‘pump or ventilatory apparatus failure’) is called hypercapnic respiratory failure. The lungs of these patients are normal. This type of respiratory failure occurs in patients with neuromuscular diseases, such as myasthenia gravis, stroke, cerebral palsy, poliomyelitis, amylotrophic lateral sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, postoperative situations limiting ability to take deep breaths, and in depressant drug overdoses. Each of these disorders involves a loss or decrease in neuromuscular function, inefficient breathing and limitation to the flow of air into the lungs. Blood oxygen falls and the carbon dioxide increases because fresh air is not brought into the alveoli is needed amounts. In general, mechanical devices that help move the chest wall help these patients.

ETIOLOGY

Brain Disorders

- Stroke: a stroke is sudden loss of brain function resulting from a disruption of blood supply to a part of the brain

- Brain tumors: a brain tumor is a localized intracranial lesion that occupies space within the skull and tends to cause a rise in intracranial pressure

- Depression of respiratory drive with drugs, e.g. narcotic tranquilizer

Chest Wall Dysfunction and Neuromuscular Factor

- Anesthetic blocking agent

- Cervical spinal cord injury

- Neuromuscular disorder

- Neuromuscular blocking agent

Airway Obstruction

- Airway inflammation

- Tumor

- Foreign bodies

- Asthma

- COPD

Interstitial Lung Diseases

- Pneumonia

- Pulmonary tuberculosis

- Pulmonary edema

- Pulmonary fibrosis

Pulmonary Dysfunction

- Asthma

- Emphysema

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Pneumonia

- Pneumothorax

- Pulmonary contusion

- Hemothorax

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

Cardiac Dysfunction

- Pulmonary edema

- Cerebrovascular accident

- Arrhythmia

- Congestive heart failure

- Valve pathology

Other

- Fatigue due to prolonged tachypnea in metabolic acidosis

- Intoxication with drugs (e.g. morphine, benzodiazepines, alcohol) that suppress respiration.

Traumatic Causes

- Direct thoracic injury may result in a number of abnormalities that can lead to respiratory failure

- Direct brain injury can result in loss of respiration

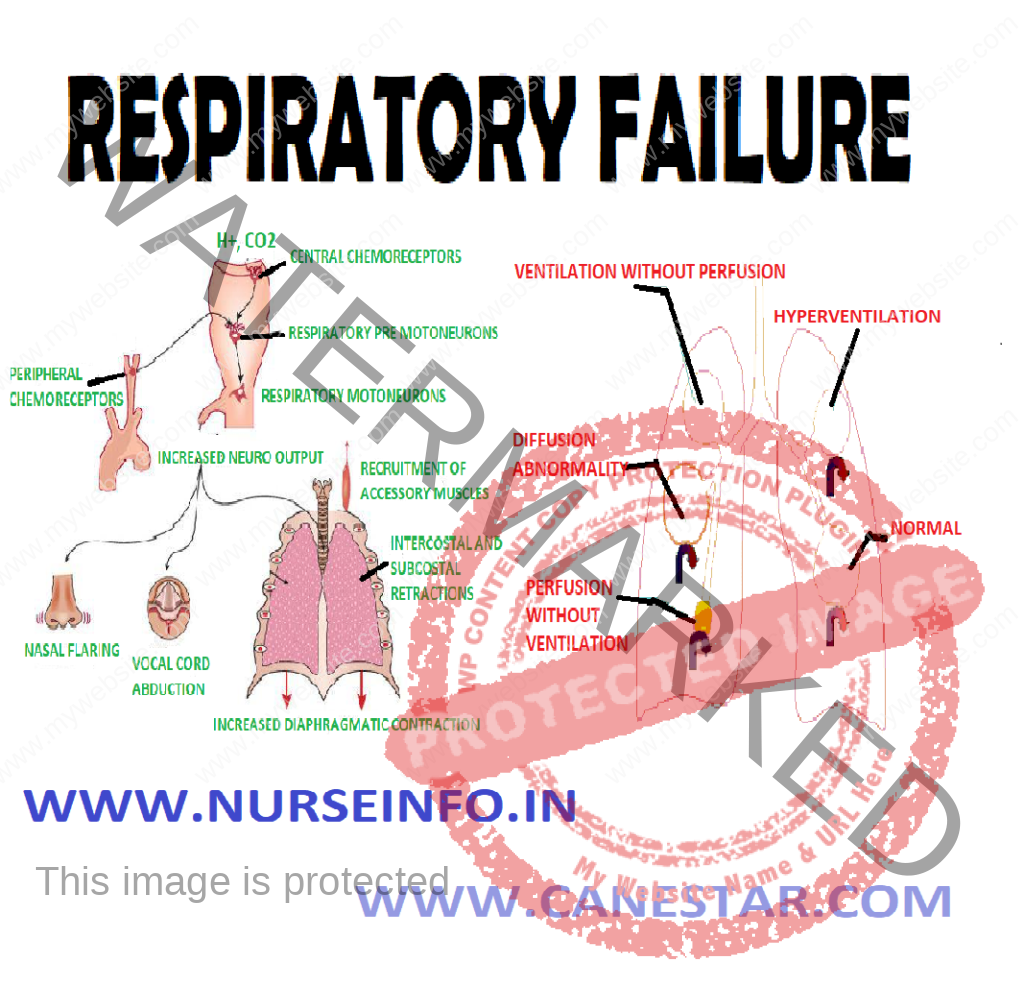

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

In alveolar ventilation —- nerves and muscles of respiration drive breathing —- failure in alveolar ventilation —- ventilation-perfusion mismatch —- hypercapnia and acidosis during obstructive forms: the residual pressure in the chest impairs inhalation —- increase in workload of breathing —- develops true intrapulmonary shunt —- decreased lung compliance

Mechanism of Pathophysiology

- Respiratory failure can arise from an abnormality in any of the components of the respiratory system, including the airways, alveoli, central nervous system (CNS), peripheral nervous system, respiratory acidosis, and chest wall. Patients who have hypoperfusion secondary to cardiogenic, hypovolemic, or septic shock often present with respiratory failure

- Ventilatory capacity is the maximal spontaneous ventilation that can be maintained without development of respiratory muscle fatigue. Ventilatory demand is the spontaneous minute ventilation that results in a stable PaCO.

- Normally, ventilatory capacity greatly exceeds ventilatory demand. Respiratory failure may result from either a reduction in ventilatory capacity or an increase in ventilatory demand (or both). Ventilatory capacity can be decreased by a disease process involving any of the functional components of the respiratory system and its controller.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

- Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

- Orthopnea

- Pulmonary edema

- Confusion and reduced consciousness may occur

- Neurological features may include restlessness, anxiety, confusion, seizures or coma

- Tachycardia and cardiac arrhythmias

- Cyanosis

- Polycythemia

- Cor pulmonale

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Right ventricular failure

- Hepatomegaly

- Peripheral edema

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

- Arterial blood gas analysis: confirmation of the diagnosis

- Renal function tests and LFTs: may provide clues to the etiology or identify complications associated with respiratory failure. Abnormalities in electrolytes such as potassium, magnesium and phosphate may aggravate respiratory failure and other organ dysfunctions

- Serum creatine kinase and troponin I: to help exclude recent myocardial infarction. Elevated creatine kinase may also indicate myositis

- Thyroid function test: hypothyroidism may cause chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure

- Spirometry: to evaluate lung capacity

- Echocardiography: if a cardiac cause of acute respiratory failure is suspected

- Pulmonary function tests are useful in the evaluation of chronic respiratory failure

- ECG: to evaluate a cardiovascular cause, it may also detect dysrhythmias resulting from severe hypoxemia or acidosis.

- Right heart catheterization: should be considered if there is uncertainty about cardiac function, adequacy of volume replacement, and systemic oxygen delivery

- Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure may be helpful in distinguishing cardiogenic from noncardiogenic edema

MANAGEMENT

Management of acute respiratory failure is dependent upon the cause and its severity. The principle of management of acute respiratory failure is the following:

- Treat the cause

- Maintain a patient airway

- Provide adequate ventilation

- Provide optimum oxygen

- Carry out chest physiotherapy

The main goal of treating of respiratory failure is to get oxygen to lungs and organs and remove the carbon dioxide from the body

The promoting effective airway clearance effective gas exchange

Preventive complication of immobility

Monitoring and documenting indication of altered tissue perfusion

Promoting comfort

Correction of hypoxemia

Correction of hypercapnia

Airway an another goal is to treat the underlying cause of the condition

Administration of Oxygen

Nasal prongs, nasal catheters, or face masks are commonly used to administer oxygen to the spontaneously breathing patient

The actual fraction of inspired oxygen depends upon:

- Flow rate of oxygen

- Degree of mouth breathing

- Patency of nasal passage

- Inspection of insertion of nasal catheter

Positive End Expiratory Pressure (PEEP)

- Used with mechanical ventilation

- Increases interthoracic pressure

- Keeps the alveoli open

- Decreases shunting

- Improves gas exchange

Management of Upper Airway Obstruction

As soon as upper airway obstruction is diagnosed, measures must be taken to correct it.

- The mouth is opened to see if tongue has fallen back or if there are secretions, blood clot or any particles obstructing the airway

- Extension of the head is the simplest way of relieving upper airway obstruction by the tongue falling back

- If simple extension of the head is not adequate to clear the airway, the mandible should be forced forward

- Maneuver is designed to put further tension on the musculature that supports the tongue. It is best executed by standing behind the patient

- If maneuver is not adequate and partial airway obstruction still exists, then oral airway may have to be inserted or end tracheal intubation be done

- If assisted ventilation is required, a resuscitator bag and mask are used initially prior to intubation and mechanical ventilation

Medical Management

Medical management includes:

- Antibiotics for pneumonia infection

- Bronchodilators: reduce bronchospasm, COPD

- Diuretics for pulmonary edema

- Chest physical therapy and the hydration to mobilize secretions

- Maintain fluid and electrolytes and avoid fluid overload

- Intubation and mechanical ventilation

COMPLICATIONS

- Oxygen toxicity if prolonged high FIO2 required

- Barotrauma may occur from excessive intra-alveolar pressure

- Ventilator-associated pneumonia

- Infection to the lower respiratory tract due to intubation

- Dental or vocal cord trauma

- Gastric complications: distension from air entering the GI tract, stress ulcers from hyperacidity and inadequate nutrition

- Other complications include deep venous thromboembolism, skin breakdown, malnutrition, stress and anxiety

NURSING MANAGEMENT

Nursing Assessment

- Note the changes suggesting increased work of breathing or pulmonary edema

- Assess breathing sound

- Assess sign of hypoxemia and hypercapnea

- Analyze the ABG and compare the previous values

- Determine hemodynamic status and compare it with previous value

Nursing Diagnosis

- Impaired gas exchange related to inadequate respiratory center activity or chest wall movement, airway obstruction, or fluid in lung

- Ineffective airway clearance related to increased or tenacious secretion

- Acute pain related to inflammatory process and dyspnea

- Anxiety related to pain, dyspnea and serious conditions

Nursing Intervention

- Improve gas exchange:

Administer oxygen to maintain PaO2 of 60 mm Hg, using devices that provide increased oxygen concentration

Monitor fluid balance by intake and output measurement, urine-specific gravity, daily weight measurement

Provide measures to prevent atelectasis and promote chest extension and secretion clearance as per advice, spirometer

Elevated head level to 30 degrees

Monitor adequacy of alveolar ventilation by frequent measurement of respiratory system

Administer antibiotic, cardiac medication and diuretics as prescribed by doctor

- Maintain airway clearance:

Administer medication to increase alveolar function

Perform chest physiotherapy to remove mucus

Administer IV fluids

Suction patient as needed to assist with removal of secretions

- Relieving pain:

Watch patient for sign of discomfort and pain

Position the head elevated

Give prescribed morphine and monitor for pain-relieving sign

- Reducing anxiety:

Correct dyspnea and relieve from physical discomfort

Speak calm and slowly

Explain diagnostic procedure