AMEBIASIS – General Characteristics, Pathology, Clinical Manifestations, Acute Amebic Dysentery, Hepatic Amebiasis and Treatment of Amebiasis

General Characteristics

The term amebiasis includes all lesions caused by infection by the protozoan parasite Entameba histolytica. These amebae cause ulcerative lesions in the large intestine causing dysentery and from there they spread to several organs to produce necrotic lesions.

There is a great tendency for the intestinal infection to become chronic and persistent for long periods. E.dispar is morphologically identical to E.histolytica, but nonpathogenic. It is genetically different. It is a commensal. However, E. histolytica can also remain in the bowel for many years without causing major symptoms.

Amebiasis is worldwide in distribution, but it is very prevalent in tropical climates. Chronic carrier state, poverty, insanitary disposal of excreta, unhygienic food handling, and proliferation of flies are responsible for this high prevalence. Though all age groups are susceptible, adults suffer more often.

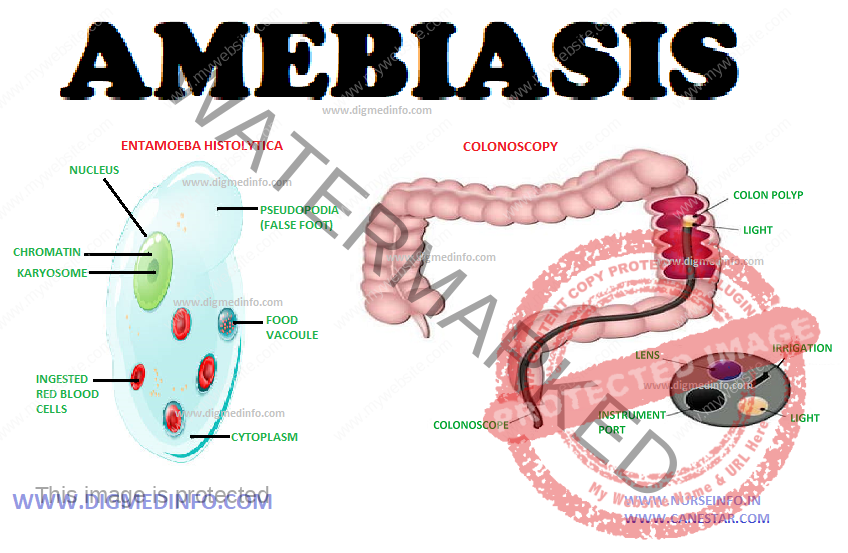

Amebae are widely distributed in nature. The common pathogen is E. histolytica. It exists in two forms—the cyst and the trophozoite. The cysts are round or oval in shape and measure 10 to 15 μ in diameter. In iodine-stained preparations the cysts show one, two or four nuclei depending on their maturity. Cysts resist adverse environment. In addition to the nucleus, one or more rodlike structures called chromidial bars, and a glycogen mass are also seen. Cysts are formed in the bowel when the environment becomes unfavorable for the trophozoite and are then passed out in feces. Cysts are responsible for transmission of the disease from person to person. The vegetative form (trophozoite) is actively motile by the aid of pseudopodia. It measures 20 to 50 μ in diameter.

Invasive trophozoites are identified by the presence of ingested erythrocytes within them. Amebae multiply by binary fission. The trophozoite is the invasive form and is responsible for all lesions. A large number of trophozoites is seen in the feces of dysenteric patients. Trophozoites and cysts occur in the feces of carriers. Outside the body, the trophozoites survive only for an hour or so. Normal gastric juice destroys them in the stomach. Cysts survive external environment for long periods.

Transmission

Humans are the only reservoir for E.histolytica. Cysts are passed in the feces of cases and carriers. These are ingested along with food or water. Cysts resist acid digestion in the stomach. Excystation occurs in the intestines, Trophozoites develop from cysts and they establish themselves in the colon, feeding on the bacteria and desquamated epithelial cells. They multiply by binary fission. These non-invasive forms may persist for long periods without producing any symptoms. Under favourable conditions these become invasive.

PATHOLOGY

Intestinal amebiasis: The invasive trophozoites adhere to colonic mucosa with the help of specific lectins and ulcerate the mucous membrane and penetrate deep into the submucosal layers of the colon. The basic pathological process is a lytic necrosis of tissue. This is due to an extra cellular cysteine kinase enzyme causing proteolytic destruction of the tissue, producing flask shaped ulcers.

E. hystolytica which produce lytic enzymes kills host cells which come into contact with them. The host cells become immobile on contact with E. histolytica, and the cells die. E. histolytica can also induce apoptosis in host cells. The cellular response consists of mononuclears and a few polymorphs. Amebae are seen in the invading margins of the lesions. Cecum, ascending and descending colon, and rectum are the sites of predilection.

The appendix may be involved. The terminal ileum may be affected rarely. The ulcers have undermined edges and are covered by dense yellow or brown slough. The mucous membrane between ulcers is healthy. Ulceration may extend to blood vessels causing severe hemorrhage at times. Perforation of the bowel may occur, but it is rare. Sometimes ameboma or amebic granuloma develop due to repeated infection by ameba and bacterial pathogens. The acute inflammatory process has a tendency to subside spontaneously.

In many patients chronic infection persists with microscopic lesions which harbour E. histolytica for many years. The lesions may heal in a few cases. Persistence of the chronic lesions accounts for the carrier state. E. histolytica infection is associated with transient immunosuppression. Activated macrophages form the major defence against invasive amebae. The resistance against invasive amebiasis is mainly cell mediated immunity.

Extra-intestinal Lesions

Amebic liver abscess: Invasive amebae reach the liver through the portal blood stream from the colon which is the primary seat of infection. In the liver they multiply and cause colliquative necrosis of liver cells to produce abscess.

Possibly malnutrition, alcoholism and consequent immunosuppression favour the development of liver abscess. Unlike pyogenic abscess, the wall of the amebic abscess is made up of necrotic and compressed liver tissue and it is devoid of granulation tissue. Active amebae are found near the expanding margins. The pus is made up of necrotic tissue which shows amorphous material and erythrocytes. It is sterile on culture.

In most cases the colour of the pus is reddish brown or chocolate. Amebae are seen only rarely in the pus aspirated from the center of the abscess, they are more often demonstrable in the pus aspirated from near the walls on subsequent occasions. The site of the abscess is more commonly the right lobe. It is usually single and may attain very large size.

The abscess may enlarge progressively and spread by contiguity to the chest wall, colon, diaphragm, pleura, and pericardial cavities. Amebic abscess does not impair hepatic-function significantly. Jaundice is generally mild or absent, but pressure over a major hepatic duct can give rise to obstructive jaundice. On aspirating the pus the liver tissue comes into apposition and complete healing occurs without structural damage or fibrosis.

During acute amebic dysentery, the liver may enlarge as a result of diffuse inflammation caused by the products of inflammation of the colonic tissue and bacteria reaching the liver in the blood stream. The hepatic lesion clears up with cure of the dysentery. This lesion should not be mistaken for liver abscess.

Other foci for embolic lesions include the lungs, brain, spleen and other tissues. Direct invasion of the skin by active vegetative amebae leads to extensive spreading necrotic ulceration-cutaneous amebiasis.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The incubation period varies from a few weeks to months.

Spectrum of illnesses caused by E. histolytica

Intestinal amebiasis

1. Asymptomatic infection

2. Symptomatic non-invasive infection

3. Acute proctocolitis (Dysentery)

4. Toxic megacolon

5. Chronic non dysenteric colitis

6. Ameboma

7. Peri anal ulcers

Extra intestinal amebiasis

1. Liver Absces

2. Pleuro -Pulmonary involvement

3. Pericarditis

4. Peritonitis

5. Brain abscess

6. Genito urinary disease

ACUTE AMEBIC DYSENTERY

This presents with sudden or subacute onset of lower abdominal pain and diarrhea with blood and mucus in stools. The frequency ranges from 3 to 10 in a day. At times watery diarrhea with large amounts of blood and mucus may occur. Constitutional symptoms are mild and these include low grade fever and vague discomfort.

Palpation of the abdomen reveals colonic tenderness and mild hepatomegaly. The feces are semisolid or liquid, showing fecal matter mixed with blood and mucus. Microscopic examination shows erythrocytes, a smaller number of leukocytes and trophozoites of E. histolytica. In the majority of cases, the condition subsides after several weeks even without treatment, to exacerbate again with dietary irregularity, psychological stress or other factors.

Complications are rare but in a few cases extensive destruction of mucosa and submucosa may lead to severe hemorrhage and occasionally perforation. Rectalprolapse, intussusception and colonic stricture may develop in some. Amebomas may develop in the cecumor other parts of the colon and these may be mistaken for tumours. These resolve completely with specific treatment.

Non-dysenteric Amebiasis

This is a common mode of presentation in endemic areas. The condition starts insidiously with abdominal discomfort, flatulence, intermittent diarrhea with constipation, and the presence of mucus in stools. Asymptomatic intervals and periods of dyspepsia alternate for many months or years. Vague general symptoms like feverishness, mild depression, fear and anxiety may be prominent. Physical examination may reveal palpable tender cecum and sigmoid and sometimes tender hepatomegaly. An amebic granuloma (ameboma) may be felt as a sausage-shaped mass in the right iliac fossa and this may be mistaken for malignancy or tuberculosis.

Mucosal ulcers may be seen on sigmoidoscopy. Examination of the mucus collected by sigmoidoscopy may show the active trophozoites. Repeated examination of fresh stool or sigmoidoscopic specimen may be necessary to establish the diagnosis. Sigmoidoscopic biopsy reveals the ulceration and the parasite in the mucosa.

HEPATIC AMEBIASIS

Hepatic involvement used to be very common, almost all patients give a history of alcoholism. Around 50% of patients suffering from hepatic amebiasis give history of dysentery. Liver involvement manifests as insidious onset of pain in the right hypochondrium or right lower chest with fever, chills and sweating. Loss of weight and anemia may be pronounced.

In the early stage the liver is enlarged as a whole. The pathological process is not inflammatory, but it consists of multiple necrotic lesions caused by amebae diffusely distributed in the liver. In this stage the organ is enlarged as a whole and it is acutely tender. This stage may persist for varying periods and may resolve either spontaneously or with treatment, without proceeding to abscess formation.

At present the occurrence of liver complications has come down. In those in whom abscess develops, the liver is considerably enlarged and tender. When the abscess spreads to the abdominal wall, there is superficial edema and severe local tenderness. The majority of liver abscesses are in the right lobe. Left lobe lesions are palpable over the epigastrium. Diaphragmatic involvement causes pleuritic pain in the right lower chest.

Physical examination reveals diminished air entry, impaired percussion note and crepitations over the lower part of the right chest. Jaundice is rare. Blood shows mild tomoderate leukocytosis (about 12-14.000/cmm) with polymorphonuclear cells dominating the field. The ESR is usually high. Fluoroscopy reveals elevation of the right dome of the diaphragm and diminished movement. Ultrasound, CT scan and isotopic scanning help to locate the site of the abscess.

Complications of liver abscess include rupture into neighbouring organs or cavities leading to peritonitis, right sided empyema, bronchohepatic fistula, and pericarditis. Untreated, the mortality may go up to 10%.

Cutaneous amebiasis occurs over the genitalia, perianal region, opening of sinuses and around colostomy wounds. Rarely metastatic lesions from the liver develop in the lungs and brain. Rupture of a liver abscess into the peritoneum causes the clinical picture of an acute abdominal emergency with shock.

Differential Diagnosis

Amebic dysentery has to be differentiated from bacillary dysentery, ulcerative colitis and tuberculous enterocolitis. Ameboma may closely resemble carcinoma. Chronic intestinal amebiasis may be mistaken for irritable bowel syndrome, diverticulitis, neurasthenia or malabsorption state. Hepatic amebiasis is a common cause of prolonged fever in the tropics and when liver enlargement and tenderness are not marked, it resembles enteric fevers, brucellosis or tuberculosis.

In an endemic area, enlargement and tenderness of the liver should suggest the diagnosis of amebic liver abscess. Other conditions such as alcoholic liver disease, primary and secondary tumours of the liver, subdiaphragmatic abscess and pyogenic liver abscess have to be differentiated. In case of doubt the diagnosis is confirmed by ultrasonography and later, aspiration. Prompt response to antiamebic drugs is a point suggesting a diagnosis of hepatic amebiasis.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Examination of the feces – Fresh stool examination by light microscopy invariably reveals E.histolytica in dysentery. Active E. histolytica shows characteristic ameboid movement and ingested erythrocytes. In chronic amebic colitis cysts are present in feces in varying numbers. These can be identified in saline preparations but cellular details are better demonstrable in iodine stained specimen. Unlike bacterial dysentery, the feces does not contain innumerable leukocytes. Plenty of erythrocytes are present. Stool occult blood may be present in invasive intestinal disease. Stool enzyme immunoassay also will be useful.

Apart from feces, vegetative E. histolytica can be demonstrated in the following specimen.

1. Liver abscess pus.

2. Sputum in pulmonary amebiasis.

3. Discharge from cutaneous amebiasis.

Serological tests – These tests are mainly used in extraintestinal disease. Indirect hemagglutination antibody test is positive in 95% of extraintestinal and 70% of intestinal amebiasis. Other tests also have been developed.

Indirect immunofluorescence is positive in more than 60% of cases. Countercurrent electrophoresis and agar gel diffusion are other methods employed.

Imaging studies:

ultrasonography – A single lesion in the posterosuperior aspect of the right lobe of the liver is commonly seen. But, multiple abscesses may also occur in some patients. Deep seated abscess may be missed on clinical evaluation. Multiple abscesses should suggest the possibility of pyemic etiology.

CT scan – In cerebral amebiasis, CT may show irregular lesions without surrounding capsule or enhancement.

Other investigations – Blood counts may show mild anemia, leucocytosis, elevated ESR and elevated alkaline phosphatase.

Endoscopy – Rectosigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy may reveal small mucosal ulcers covered with yellowish exudates, and the intervening mucosa appears normal. For demonstrating vegetative amebae the fresh mucus exudates should be examined as a saline preparation, microscopically.

In chronic intestinal amebiasis the feces show amoebic cysts, when the disease is quiescent. With acute exacerbation, trophozoites appear from time to time. Charcot-Leyden crystals may be seen as a result of chronic bleeding foci. These crystals are needle shaped, refractile, and are made up of lysophopholipase.

TREATMENT OF AMEBIASIS

Drug treatment consists of amebicidal drugs. These may act on the parasites found in the lumen of the gut or on the invasive forms seen in the tissues. They are grouped as luminal amebicides and tissue amebicides. Some drugs, however, have action on both sites.

Prevention:

The most important steps are to observe food hygiene, provide safe drinking water and arrange for sanitary disposal of human excreta. Ordinary chlorination of drinking water does not kill the cysts. Cooks and food handlers should be periodically examined and the infection eradicated. Fruits and vegetables can be rendered safe by washing with soap and peeling off the skin wherever possible.